Mast Brothers: What Lies Behind the Beards (Part 2, Equipment)

Skepticism about the Mast Brothers’ early bean-to-bar claims also arose from their equipment—specifically, whether it was capable of producing the variety and quantities of chocolate that they put on the market. The Mast Brothers equipment set-up can be divided into three periods over their first years in business: black box, transitional, and permanent.

(After repeated requests to Rick Mast for an interview at a time and place of his choosing, his public relations representative declined on his behalf.)

The black box phase began in early 2007 (at which point the Masts were only making crude truffles, not the bars for which they came to be known), continued to their incorporation in October of 2007 (after which the bars began appearing), and then through to early winter of 2008. Most of this time, the Mast Brothers operated in Michael Mast’s crowded Williamsburg apartment on Bartlett Street. With a roommate and three girlfriends sharing the space, the Masts found the “headquarters pretty tight,” in addition to being “illegal” (Mast Brothers Chocolate: A Family Cookbook, p. 27; hereafter, MBC). By July of 2008, the Masts relocated to a larger apartment and began operating in 300 square feet of space at 260 Morgan Avenue in Greenpoint (MBC, 121; “Taking a Bite of Brooklyn,” New York Post, Chris Erikson, July 14, 2008).

Rick Mast making truffles in Williamsburg apartment “factory” (February 2007)

During the black box period, the Mast Brothers drew intense media interest—more, in fact, than any American bean-to-bar chocolate maker in business at the time. They received flattering attention from Time magazine, the New York Times, New York Post, Time Out New York, The New Yorker, New York Sun, Z!nk, Conde Nast Traveller, Cool Hunting, Brooklyn Based, Edible Brooklyn, Serious Eats, and more. In April of 2008, Rick Mast told Time, “We actually have over 250 accounts on a waiting list across the country, so it’s just getting crazy. We barely have time to make everything” (“Chocolate Adventures: Brooklyn’s Dark Secret,” Paige Reddinger). By the end of 2008, their bars were sold by at least ten retailers in and around New York, as well as in shops in Georgia, Colorado, Minnesota, California, Massachusetts, and New Jersey. The Masts were supplying chocolate to celebrity chefs, like Dan Barber and Thomas Keller.

In their IACP award-winning cookbook, the Mast Brothers stated that one of the core principles of their business has been to “Be honest and transparent. We demand integrity in everything we do and eagerly open ourselves up to the world with pride. That’s why we opened a craft chocolate factory in the middle of New York City!” (MBC, 5). Yet, during their black box phase, there was almost no public information about how the Mast Brothers were making all of this chocolate. They maintained a company web page, a blog, and a MySpace account; but none showed a single photo or video of chocolate-making equipment. This was unusual, to say the least. Following the NōKA Chocolate scandal of late 2006, American chocolate makers were taking every opportunity to educate their customers about—and to show—the equipment and labor required to make chocolate from the bean. Transparency had become a crucial marketing tool for craft chocolate makers. Not so, for the Masts.

Mast Brothers in Greenpoint loft, by Tiffany Hagler-Geard (July 9, 2008)

Media reports from the time offered almost no additional detail. In a Brooklyn Based article from March of 2008, Nichole Davis wrote that the Masts “roast and winnow off their husks with makeshift tools like coffee roasters and hair dryers, then grind the beans superfine.” A July 2008 image by photographer Tiffany Hagler-Geard (for a New York Post article) showed the brothers—then in the 300 square foot Greenpoint space, having left their Williamsburg apartment—posing with a half-empty bag of Dominican cacao and a ChocoVision Revolation tempering machine (with a coffee roaster in the background and a juicer sitting on a shelf below). Astonishingly, given the amount of New York-based media coverage during this period, no journalist reported having seen the Mast Brothers make chocolate.

Michael Mast posted scores of photos to a popular image-sharing site during this time. Some of the earliest are of Rick Mast making truffles in their Williamsburg apartment and of the brothers boxing them up for sale. Many more are of finished bars in the Florentine wrapping paper (by Rossi) that came to define their brand. There are some, in spring of 2008, of the brothers posing for publicity shots with their new faux-Amish look and a half-empty bag of Dominican cacao. It’s not until September of 2008—near the end of the black box period—that Mast posted a picture of chocolate-making equipment (i.e., a CPS Limited winnower).

Little Masts on the Prairie (April 2008)

Since so little is known about the equipment the Masts might have been using, no firm conclusions can be drawn from their apparent success in meeting heavy, media-driven demand and supplying numerous wholesale accounts from an incommodious apartment kitchen or a 300 square foot loft. However, their vast product line through this period raised eyebrows, at the time, and remains difficult to reconcile with bean-to-bar production. Every distinct type of chocolate requires making a batch. Making a single batch can tie up a melangeur for days. This is why most craft chocolate makers have a fairly limited range of bars available, often no more than a handful. Throughout 2008, the Mast Brothers were typically selling between ten and fourteen different types of bars, using many distinct types of chocolate. They almost always sold milk chocolate, sometimes without specifying the percentage of cacao solids, sometimes as 60%, sometimes as 65%. Through the first half of 2008, they sold a white chocolate bar. They sold bars of unspecified cacao origin, sometimes with unstated percentage, sometimes at 70%, 72%, 75%, or 81%. And they sold single-origin bars with cacao from Ecuador, Madagascar, Venezuela, Dominican Republic, and Trinidad, in a range of percentages (64%, 66%, 70%, 72%, 75%). Without a fleet of grinders (such as the Masts began building up from mid-2009) working around the clock, it’s hard to envision how the Masts could make the number of batches required for the variety of chocolates they were selling; and their cramped quarters would not have accommodated that much equipment.

The Mast Brothers’ transitional phase began with their move into a larger space at 105A North 3rd Street (in Williamsburg) near the end of 2008, and continued until May of 2009. In February of 2009, the new facility opened to the public for limited hours on the weekends for direct retail sales, on a cash-only basis. In a move towards greater transparency, the Mast Brothers also began allowing some visitors in to see the operation.

In recent years, Rick and Michael Mast have boasted of the novelty of what they were doing and how they were doing it. Rick Mast said, “We’ve had to come up with how everything is done every step of the way because there was no such thing as small-batch chocolate makers” (“The Mast Brothers,” The Weekend Edition, Mikki Brammer). Setting aside the question of whether the Mast Brothers actually were chocolate-makers at this time, this is simply false. As Shawn Askinosie pointed out earlier this year, a number of American chocolate-makers entered the market before the Masts, including Askinosie, DeVries, Taza, Amano, Patric, and Rogue. Earlier still, in 2003, John Nanci launched his influential Chocolate Alchemy web site, becoming the prime mover of modern small-batch chocolate. Nanci laid out the processes and equipment—evolving through contributions of active participants of the online community he built—that are now used by most chocolate makers in America today, including the Masts.

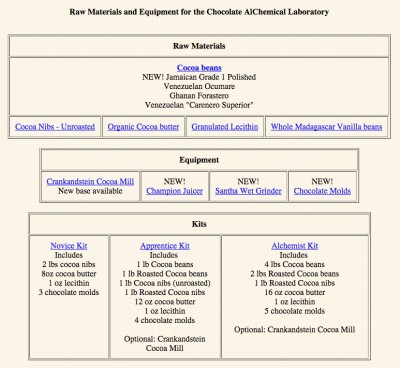

John Nanci’s chocolate-making kits (January 18, 2006)

In an interview earlier this year, Rick Mast said, “When we started we were pretty much having to invent or re-purpose every little bit of equipment that we were using” (chocolatier.uk, Jenny Linford). In a 2010 radio interview with Jessica Harris (“From Scratch,” NPR), he said, “There’s no such thing as commercial equipment for [small-batch chocolate making]. You can’t say, I’m going to start a small chocolate company and then go online and get a couple of machines.” Similarly, Michael Mast wrote that, “There was no chocolate kit to speak of” and that “there was no standard equipment to use” (emphasis in original; MBC, 121). But there actually were chocolate kits and standard equipment. John Nanci sold them on the Chocolate Alchemy web site as far back as 2004. Photos from the North 3rd Street shop, during this transitional period, show that the Mast Brothers slavishly followed the John Nanci playbook.

For roasting, the Mast Brothers initially had a Behmor 1600 Coffee Roaster (with capacity of under three pounds per batch). Though not a piece of equipment manufactured for roasting cacao, John Nanci discovered its suitability for cacao, experimented with it, developed roasting profiles for it, wrote about it, and began selling it to small-batch chocolate makers well before the Masts began appearing at weekend markets in late 2007. During their transitional phase, the Masts traded “boxes and boxes of chocolate” for a Moffat Turbofan convection oven from the owners of Marlow & Sons (MBC, 123). John Nanci discussed oven-roasting of cacao, including times and temperatures, as far back as 2003, with Chocolate Alchemy community members sharing their experiences and tips in the years that followed.

Crankandstein Cocoa Mill (photo by George Gensler, March 2009)

As a sign of the brothers’ creativity and resourcefulness, Michael Mast wrote that, “We cracked the cacao shells with a hand mill used for crushing barley in home brewing” (MBC, 123). Photos reveal that this was, in fact, a Crankandstein Cocoa Mill. This piece of equipment was not only specially manufactured for small-batch chocolate makers (hence the name), but was developed by the manufacturer in direct collaboration with John Nanci, who was responsible for the gap dimensions, the three-gear system, and elimination of the slave roller. All of this was done nearly two years before the Masts sold their first bar of chocolate. Making his failure to give credit even more audacious, Michael Mast purchased his Crankandstein Cocoa Mill directly from John Nanci on March 13, 2008.

For winnowing, during the transitional phase, the Masts shifted from hair dryers (recommended by John Nanci from 2003) to a CPS Limited Cocoa Bean Winnower. This was another piece of equipment specially manufactured for small-batch chocolate makers, recommended and discussed by Chocolate Alchemy forum members for nearly a year before the Masts’ transitional phase.

Michael Mast wrote that, “At times we used juicers to break down the nibs into a chocolaty paste before adding sugar and grinding” (MBC, 123). Photos show that the Masts had a Champion Juicer. This is, not coincidentally, the exact piece of equipment recommended by John Nanci for this purpose and sold on his web site since early 2004.

Santha melangeurs for chocolate-making (August 2007)

Michael Mast described using “twenty- and forty-pound wet grinders,” claiming that “the grinders weren’t even made for chocolate” (MBC, 123). Photos of their shop show that the two grinders they had were Santha Spectra 20 and Spectra 40 stone melangeurs. From the initial release of those models over a year before the Masts began selling, Santha’s web site expressly marketed them as “stone melangeurs for chocolate making.” Yes, they were “made for chocolate.” Moreover, they were developed by the manufacturer at the specific request of—and with nearly two years of design input from—John Nanci. Nanci’s collaboration with Santha was so vital that the company named its first dedicated chocolate-making model the “Alchemist’s Stone” melangeur.

For tempering, photos show that the Masts used the same machine they had during their black box phase, a ChocoVision Revolation X3210. Because of its low capacity (i.e., ten pounds of chocolate), this was another piece of equipment manufactured specifically for small chocolatiers and chocolate-makers. Though Nanci never sold ChocoVision temperers, the pros and cons of this model and others were frequently discussed in the Chocolate Alchemy forums.

Knowing the equipment the Masts used in this transitional period does more than debunk their specious boasts of originality. It reveals the range of limits of their possible production, both in numbers of batches and in quantity.

Assuming minimal refining time of about 48 hours in the Santhas (even though that would be hard to square with the remarkably smooth texture of their chocolate at the time), no shortage of labor to handle any equipment, no loss, operating the equipment at full capacity (even though doing so would reduce efficiency) twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, with no downtime during or between batches (however impossibly), this set-up could produce no more than 7 batches per week, for a total of 1,344 bars.

That’s a lot of chocolate for a small maker. But since a batch is required for each distinct type of chocolate, it’s not enough to account for the broad variety of chocolates the Masts produced. Nor does it achieve the quantities they have said they produced at that time.

In Mast Brothers Chocolate: A Family Cookbook (2014 James Beard Award finalist), Rick Mast vividly recounts the story of “a surprise visitor” to their shop. While the brothers were scrambling to fulfill wholesale orders during the Christmas season, Thomas Keller appeared at the factory. He was “immaculately dressed, in a perfectly tailored dark wool overcoat with a crisp red scarf.” Keller said, “I’ve been doing some Christmas shopping and wanted to stop by and see your factory before I head to the airport back to Napa Valley. Let me introduce you to our chef at French Laundry, Corey Lee” (MBC, 205). Though Rick Mast doesn’t provide a date for the meeting, Corey Lee’s departure from the French Laundry in the summer of 2009 places his and Keller’s visit around Christmas of 2008—near the beginning of the Masts’ transitional period. Describing the feverish pace of production at that time, Rick Mast writes that “The Park Slope Food Coop alone was ordering more than 3,000 chocolate bars a week!” (MBC, 205; exclamation point in original).

Week after week, one wholesale account was ordering more than double what the Masts could have possibly produced from the bean with the equipment they had, even with improbably charitable assumptions; yet the Masts’ web page at the time showed that they had at least fifteen wholesale accounts that Christmas season.

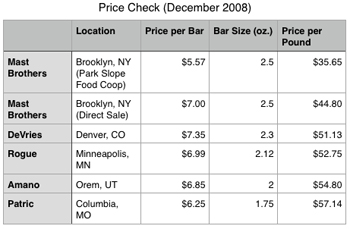

At that time, the Park Slope Food Coop sold Mast bars for $5.57 each, following the co-op’s policy of a 21% markup over wholesale pricing. The Masts sold their bars to the public for $7 each. Their pricing adds to the puzzlement in a couple of respects. First, the Masts’ retail prices by weight were significantly lower (12% to 22%) than those of then-established bean-to-bar chocolate makers in America, such as Amano, Patric, Rogue, and DeVries, all of whom operated with narrow margins in cities with much lower overhead than Brooklyn, New York. Second, although their product was—as the Masts repeatedly attested to the media—in extremely high demand, they sold most of it wholesale, sacrificing much larger profits from retail sales. When Thomas Keller and Corey Lee interrupted their frantic fulfillment of holiday wholesale orders, Rick Mast writes that, “We found ourselves turning away customer after customer, even putting a ‘Sold Out’ sign on our front door in December!” (MBC, 205). Had they taken down that sign and satisfied local demand directly, the Masts would have more than doubled their profit on every bar. Instead, they excluded the public from the shop and kept tempering chocolate for the wholesale orders. The Masts’ low prices and preference for wholesale sales (despite strong local demand) were nearly inexplicable, in light of the economics of small-batch bean-to-bar chocolate.

At that time, the Park Slope Food Coop sold Mast bars for $5.57 each, following the co-op’s policy of a 21% markup over wholesale pricing. The Masts sold their bars to the public for $7 each. Their pricing adds to the puzzlement in a couple of respects. First, the Masts’ retail prices by weight were significantly lower (12% to 22%) than those of then-established bean-to-bar chocolate makers in America, such as Amano, Patric, Rogue, and DeVries, all of whom operated with narrow margins in cities with much lower overhead than Brooklyn, New York. Second, although their product was—as the Masts repeatedly attested to the media—in extremely high demand, they sold most of it wholesale, sacrificing much larger profits from retail sales. When Thomas Keller and Corey Lee interrupted their frantic fulfillment of holiday wholesale orders, Rick Mast writes that, “We found ourselves turning away customer after customer, even putting a ‘Sold Out’ sign on our front door in December!” (MBC, 205). Had they taken down that sign and satisfied local demand directly, the Masts would have more than doubled their profit on every bar. Instead, they excluded the public from the shop and kept tempering chocolate for the wholesale orders. The Masts’ low prices and preference for wholesale sales (despite strong local demand) were nearly inexplicable, in light of the economics of small-batch bean-to-bar chocolate.

Mast Brothers’ CocoaTown ECGC 65s

Towards the summer of 2009, the Masts began moving to the permanent equipment set-up that most visitors to their factory have seen. In May, they started acquiring their fleet of CocoaTown ECGC-65 melangeurs, each of which, individually, had more capacity than the two old Santhas combined. They began using a higher-capacity Selmi temperer. (Before that point, Michael Mast says that their production bottleneck was in tempering, not grinding [MBC, 177].) By fall, they obtained a prototype of a vortex winnower invented by Daniel Preston and Steve Chelminski of Brooklyn Cacao. Visitors to the shop could finally see chocolate being made in credible quantities. It was also around this time, as previously noted, that attentive observers discerned significant changes in the characteristics and quality of the chocolate the Masts sold.

[Go to Part 1, Part 3, or Part 4. Supplemental matter will appear on the DallasFoodOrg Tumblr.]

To read dallasfood.org